"Prove to me you're the man" An Analysis of Gender and Sexuality in 'Final Fantasy VII'

Also known as my longwinded excuse for saying why Cloud Strife is trans.

Introduction

With the upcoming release of Final Fantasy VII: Rebirth, my mind is filled with nostalgia for the original game. While I personally never played it, having not been born at the time of release, my first introduction to Final Fantasy was from the Japanese role-playing game Kingdom Hearts. In Kingdom Hearts, Disney characters and Final Fantasy characters come together with a group of children to fight off evil forces known as Heartless. While playing as the happy-go-lucky Sora, I was enthralled with Cloud’s mysterious and brooding persona. When we’re introduced to him in Olympus, Cloud is an antagonist working with Hades to presumably bring someone back from the dead. It wasn’t until my late teens that I decided to learn about Final Fantasy VII by watching playthroughs of it on YouTube. I was shocked to find that the image of Cloud Strife presented to me in Kingdom Hearts—a cape-wearing, sword-swinging assassin—was only scratching the surface of the original Cloud. Cloud’s mysterious and brooding persona was not just a fact of life, but rather the product of extensive trauma during his time in military service as a SOLDIER.

In a critical essay on transmedia game characters, Joleen Blom argues that “Players lose their creative agency over the development of the dynamic game characters once it transfers to another medium or story due to the ideal of the narrative continuity of transmedia storytelling” (151). In other words, when characters are transferred across mediums, players no longer have control over how these characters function because the character is now confined to the constraints of this specific world and its narrative requirements. This is especially so in the case of crossover games, where games from another gaming franchise are placed into a different game. However, Blom goes on to say that this does not necessarily mean that dynamic characters lose their nuances when in crossover media. For example, fighting games often have crossovers with other video game franchises and, due to their nonlinear storytelling, have to find unique ways for these characters to feel inclusive to the story without damaging the active storyline. Thus, players must use their innate knowledge of the crossover series to understand the characters in this new context. I would add that the supplemental information that these players use can be biased based on their reading of the original game. In the original Final Fantasy VII and the subsequent prequel game, Final Fantasy VII: Crisis Core, Cloud is portrayed as having once been a shy and self-conscious young man who doubts his place in the hyper-masculine world of SOLDIER, and later becomes brooding and withdrawn after defecting from his military status. This character arch can be understood as Cloud going from being feminine to performing masculinity and ends with a synthesis between both sides. However, media portrayals of Cloud, including the Square Enix game Kingdom Hearts and his portrayal in the Nintendo game, Super Smash Brothers, go back on these portrayals of Cloud and construct him as being purely masculine to fit. Final Fantasy VII can be read through a transformative queer lens that showcases how gender and sexuality are troubled by Cloud Strife in his journey of self-discovery, however, due to the writer’s implicit misogyny, transmedia readings of Cloud limit him to the hypermasculine persona that the game perpetuates early on.

Partying Like It’s 1997

Final Fantasy VII was first released on January 31, 1997, in Japan and nine months later in North America. According to an IGN article by Rus McLaughlin, “Final Fantasy VII sold over two million copies in its first three days in Japan alone” (2008). This overabundant popularity led to an early release into North American markets to continue the positive reinforcement. Following the story of Cloud Strife, VII examines the effects of social inequities on our society but places this in the context of a hyper-futuristic fantasy world complete with monster weapons and a magic system. AVALANCHE, an ecoactivist group, is led by Barret Wallace and Tifa Lockhart. Their mission is to fight the fictional government entity, Shinra Electric Company. Tifa is the one who contacts Cloud as a mercenary to help carry out missions to thwart Shinra’s attempts at subjugating the lower classes who live below their metropolitan city. AVALANCHE intends to force Shinra to stop harvesting energy from the LifeStream, the essence of the planet and the souls of those who have passed on. However, things become more complicated as AVALANCHE finds themselves not only saving the planet from Shinra but also from Sephiroth, a former SOLDIER who now plans to destroy the planet as payback for becoming a monster. It becomes clear how this game appealed to so many people across the world. Players were comforted by familiar narratives of rebels fighting against corrupt governments, formidable villains with dramatic backstories, and a cast of characters all with their own storylines. Duncan Heaney writing for Square Enix also makes these same conclusions, while adding that the strong soundtrack and unique gaming conventions allowed Final Fantasy VII to stand out from its competitors. He contends that “The game is full of unforgettable character moments, like Red XIII’s journey of discovery in Cosmo Canyon, or Cid’s anger and depression over his failed dreams of space flight to name but [two]” (2022). The emphasis on character work also extends to how they were designed as

“[Tetsuya Nomura] sweated every detail. Tifa Lockhart came in as romantic competition for Cloud's affections; Nomura obsessed over the length and color of her skirt to counterpoint Aerith's long pink dress, and nearly settled it by putting her in pants. The new Cid, a staple since II, became a foul-mouthed chain smoker. Talking lion Red XIII gained tattoos and a Native American motif before Nomura set his tail on fire for a little extra color. Ninja thief Yuffie Kisaragi and mechanical puppet Cait Sith added the requisite cute factor, while brooding Vincent Valentine's background changed from horror researcher to detective to chemist to undead man of mystery” (McLaughlin 2012).

Rather than focusing solely on Cloud, director Yoshinori Kitase and co-writer Kazushige Nojima give agency to each character within the party, granting them a humanity that might otherwise be ignored by most players. This is carried over into the next main title game released ten years later on September 13, 2007, Final Fantasy VII: Crisis Core.

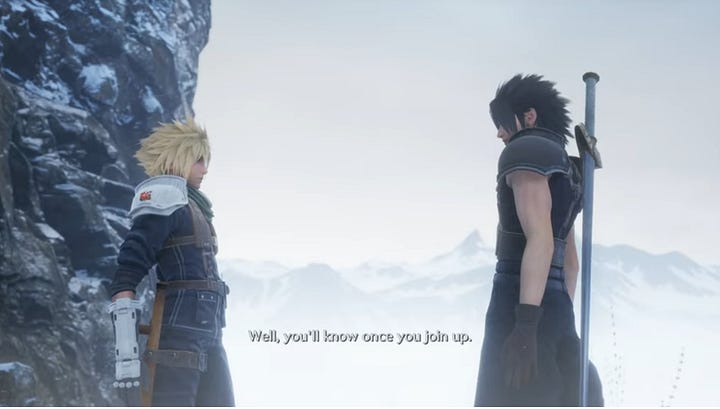

This game serves to build the foundation that the franchise established in 1997. In Final Fantasy VII, it is revealed that Cloud served at the same time as Sephiroth and another man named Zack Fair. Zack is everything that Cloud is not—charismatic, friendly, and light-hearted. Yet, when Cloud describes his memories of being a First Class SOLDIER in the original game, his actions mimic that of Zack. Players get the inkling that something is awry early on, but the reveal isn’t made until the real Sephiroth is resurrected from his entrapment in crystal. The memories that Cloud has been claiming as his own up to this point are actually his memories of Zack. The real Cloud was a lower-class soldier who got caught in the crossfire of Sephiroth’s meltdown after Sephiroth realized that he was created by Shinra from the essence of a space alien they captured. After stabbing Sephiroth and leaving him to fall into a mako reactor, Zack and Cloud escape while Cloud is unconscious. The two meet an ugly end as Zack is slain by SOLDIERs, leaving Cloud to inherit his legacy. The memories that Cloud experiences are caused by Jenova, the alien being that was used to birth Sephiroth as a supersoldier and who masquerades herself as Sephiroth until she can free her son from his imprisonment. Crisis Core illustrates Zack’s life up until his untimely demise—showcasing his connections to Aerith Gainsborough, Cloud, Sephiroth, and a few additional characters who set the precedent for the events to come.

As far as reception goes, while Crisis Core did not receive the same overzealous support as its predecessor, it did sell 350,000 copies upon release and was the best-selling game in all regions of Japan from April until September (Powell 2007). Once again, reviews for the game were high and once again, players seemed enthralled by the story, though this time it was because of its connection to the original game. Colin Steven writing for IGN states that “The events that transpire in Crisis Core add intriguing depth to Cloud, the Turks, and many other characters from Square’s beloved classic and its remake – Sephiroth, in particular, becomes much more humanized during its runtime” (2022). With this in mind, one can see the polarizing influence that Final Fantasy VII had on a generation of RPG fans. This game was crucial to many people’s development, mine own included, and is a staple of pop culture to this day. Yet, when you look at the fanbase of Final Fantasy VII, you will find a shocking majority of them are men.

Final Fantasy VII is part of a long line of games within the Final Fantasy series though none of them are related except for the spin-off games connected to a specific numbered title. In other words, you can play Final Fantasy VII without having played Final Fantasy or Final Fantasy II, but you would be remiss to skip out on playing Crisis Core. In all of these games, the protagonists are male with some female party members. The first playable female character in a Final Fantasy game didn’t come until Final Fantasy VI with Terra Branford and later Lightning Farron in Final Fantasy XIII. However, the games reverted to their male origins shortly after in Final Fantasy XV and XVI, with XV even going as far as to have an all-male playable party. The female fans that do exist discuss how the advent of characters like Aerith and Tifa was monumental for them. These were characters who were playable and had realistic personalities unlike in some other popular games at the time. One female fan, Kathryn from the blog Contemporary Japanese Literature, states that the Final Fantasy games generally became less focused on male protagonists to appeal to female fans who “come to the series looking for fully developed characters and intriguing stories, not just two-dimensional paper cut-outs going through the motions of a fantasy-themed farce” (2011). Rather than having female characters who existed solely to be objects of affection for the male protagonist, Aerith, Tifa, and Yuffie were unique and intricate women with developed backstories. A martial artist who is reserved but dedicated to saving the planet, a flower girl in poverty who is the last living person of her alien race, and a ninja trained under the tutelage of her father and desperately trying to avoid the conflict ongoing in her country. While these characters are monumental for the period in which they were made, it does stand to question whether the narrative of Final Fantasy VII itself was entirely as feminist as nostalgics make it seem.

Becoming a SOLDIER Boy

The concept of SOLDIER, the fictional military in Final Fantasy VII, is the pinnacle of what is expected of a man. SOLDIERs are strong, courageous, obedient, and orderly. We see more of this portrayal in Crisis Core with Zack Fair. Zack is the epitome of a promising SOLDIER with dreams of joining the highest rank—First Class. Zack is loyal to his brotherhood, physically strong, and chivalrous to women. As you play Crisis Core, you realize that there are no female SOLDIERS. Yes, there are female Turks, but the Turks are a special agent task force occasionally working with the military, similar to the C.I.A. by US-American standards. SOLDIER, which is more comparable to the common military, does not have any female participants save for those who work on the desk as receptionists and accountants for Shinra Electric Company. Thus, like the real-life military, we can see how SOLDIER is a symbol of masculinity and male performance. This masculine essence is present in all SOLDIER members of high status, with those who go against the grain— those who are weak and don’t desire to work as hard—being shamed by the others.

An example of one of those hyper-masculine superiors is Zack’s mentor, Angeal Hewley. Angeal has the same basic characteristics of honor and loyalty as Zack but leans more into the imagined and idealized stoic form of masculinity popularized by mainstream media. He wields the illusive Buster Sword, a custom blade of immense size and girth. His decorum extends to the battlefield, as Angel refuses to use the sharp end of his blade for fear of it causing rust, wear, and tear. Rather, he prefers the blunt end to incapacitate his enemies instead of killing them. Angeal is popular enough to have a fan club, both in the real fandom and in the fictional world of Midgar, and is undeniably meant to overpower Zack in terms of masculine essence. Zack is still a man but is not mature enough as he’s consistently compared to a puppy by other characters in the series. Meanwhile, Angeal is mature to the point of seeming emotionless as he holds up his brooding persona even after he’s doomed to the fate of becoming a monster. His rugged appearance of slicked-back hair, a thick beard on his chin, and muscular physique mark him as a man and contrast him against his counterparts of destruction—Genesis and Sephiroth.

Unlike Angeal and Zack, Sephiroth and Genesis are displayed as having feminine features—long hair, slender faces, and delicate hands. Even their weapons display this contrast as Sephiroth wields a katana named Masamune, a slender and elongated blade that keeps distance from his target. While yes, swords are seen as phallic symbols that can be associated with masculinity, there is still a clear divide in the visuals of each sword and the styles in which they’re wielded. Sephiroth is graceful, angelic, and elegant. Though his damage is violent, he does so while floating and jumping using his singular wing. What makes this even more intriguing is that the Sephiroth we are following in the original Final Fantasy VII is Jenova—a woman. The real Sephiroth, the one that Cloud fights at the game's end and the one introduced to us in Crisis Core, is showcased through a newfound lens of hypermasculinity. He’s shirtless in the final battle, dressed only in leather pants and boots. Suddenly, we are forced to acknowledge Sephiroth’s male physique and performance.

While some of Sephiroth’s feminine traits are most likely attributed to Jenova, there is still something troubling about the dichotomy presented. Take, for instance, Genesis, who has no discernible attachment to Jenova nor was imitated by Jenova. Genesis, like Sephiroth, has a softer, poised, and coiffed appearance. Further, he also wields a thin rapier and has nimble reflexes in combat. Again his damage is prolific and again he does so while appearing emotional and snarky rather than stoic and brooding. He recites poetry as he annihilates and almost seems to be acting on a stage more than he is living in reality. All of these attribute themselves to a more feminine disposition that serves as markers of his villainy. It goes without saying how the practice of crafting male villains that are hyper-feminine has long existed and has been well documented as an after-effect of writers wanting to write queer (read as gay or transfeminine) characters but struggling to do so due to censorship law. However, this also leads to a negative connotation of associating queerness with villainy. When your hero is hypermasculine and your villain is hyperfeminine but both are men, one must wonder what the author finds dubious about a man who presents femininely. I don’t necessarily think that’s the case here, but it’s important to note that Sephiroth and Genesis are not novel examples of this phenomenon. Where things become more interesting is how this is reflected in the main storyline of the first game.

Ex-SOLDIERs Still Cry

As mentioned previously, Crisis Core is a prequel game in the Final Fantasy VII franchise written ten years after VII’s initial release. However, what is described in Crisis Core can still be felt in the original Final Fantasy VII. When Cloud is first introduced, he falls into the stereotypical concept of masculinity that Angeal possesses. He’s stoic, strong, unyielding, and devoid of emotion. He contrasts the sensitive Tifa and the rage-filled Barret, who mark his lack of emotion as being a result of his SOLDIER occupation. Once again, we see SOLDIER as this symbol of what a man should be. While Barret does reflect another masculine ideal—one that is ruthless while still nurturing, as he cares for his adoptive daughter Marlene—he is still put at odds with Cloud because of his emotional instability. Barret is too violent and too irrational to be considered a proper man, hence why Cloud’s calm composure and icy personality are preferred by most players and by female characters in the narrative.

However, it is later revealed in the game that Cloud’s emotionless disposition is not just a byproduct of being a SOLDIER, but comes from his injection with Jenova cells and the loss of his mentor and best friend, Zack Fair. On his deathbed, Zack makes the ultimate manly sacrifice, just as Angeal did for him, and asks that Cloud continue his legacy. Cloud does the only thing he can think to do, perform masculinity as was presented to him by Zack. Cloud in Crisis Core is depicted as being leagues away from his initial portrayal in the original game. Cloud in Final Fantasy VII does not care about the planet's plight and instead only helps as an IOU to Tifa, his childhood friend. Yet, Cloud in Crisis Core is younger and much more subdued. He doubts himself and his abilities as a SOLDIER and becomes ashamed of being a lower class. To this end, Zack inspires him to try harder and reminds him that he wouldn’t have been able to join SOLDIER in the first place if he wasn’t worthy.

Zack reaffirms the masculinity that Cloud believes he lacks inherently, thus it comes as no surprise that Cloud later uses Zack’s sparkling rapport as a safety net after becoming possessed with Jenova cells and developing amnesia. He takes on the memories of Zack—his heroism, his passion, his status—and claims them as his own so that he can feel like a man. This is reinforced in the original game, where Cloud is depicted as a friendless child who struggles to connect with others, save for Tifa. Tifa is protective of Cloud, recognizing his lack of masculinity, and makes up for what he lacks until Cloud can stand on his own. When Cloud becomes incapacitated after freeing the original Sephiroth from the mako reactor, it is Tifa who looks after him and ultimately must enter his mind space so Cloud can come to terms with his true self. Once again we see Cloud as being feminine and weaker, hence why he relies so heavily on Zack to perform masculinity later in life. Despite Tifa being a juxtaposition to Cloud in terms of masculine/feminine energy, the writers do not let her become too masculine for fear of ignoring her womanhood. Tifa resigns her fate to being a damsel in distress after Cloud decides to join SOLDIER in his teenage years, asking that he save her when she’s in a bind as repayment for leaving her behind. For Cloud’s masculinity to flourish in the narrative, the gender binary must be enforced on all characters. This means female fighters like Tifa and Aerith are overshadowed by an overbearing feminine energy that positions them as weaker than their male counterparts.

Just a Flower Girl

While researching public opinion on how gender is performed in Final Fantasy VII, I came across an article titled “Feminism and Final Fantasy” from the blog Contemporary Japanese Literature. The author analyzes female characters from various Final Fantasy games in multiple posts and concludes that “the Final Fantasy games have become progressively less phallocentric with each successive installment in the series” (2011). Of course, hindsight is 20/20. At the time Kathryn was writing, the Final Fantasy XIII series was just taking off and she could not foresee the phallocentricism that Final Fantasy XV and XVI would take on. Despite this, Kathryn is not wrong in saying that we have come a long way in terms of how women are treated in Final Fantasy games. However, her analysis seems to fail in understanding the character of Aerith Gainsborough. Kathryn argues that Aerith is a “Mary Sue,” claiming that “the short paragraph of text in the game’s manual describes her as “mysteriously beautiful,” [having] an exotic name, she has an unusual and dramatic back story, she’s exceptionally talented in a wide variety of areas and possesses rare powers, she is the last of her race, all of the game’s characters (even the markedly antisocial ones) adore her, she is brave, cheerful, and incorruptible, she is too pure for this earth and sacrifices herself to save everyone, and her only flaws, innocence and naivety, are far from damning.”

Rather than giving Aerith a fair chance, the author relies on exhausted fandom principles to understand Aerith’s weight in the narrative. For those uninitiated, a “Mary Sue” is a common argument in fan critiques of female characters. Though the term lacks a stable definition, some common traits associated with Mary Sue characters include being overpowered in terms of skill or ability, being flawless to the point of perfection, and being romantically pursued by all male characters. The label of a Mary Sue is grounded in misogyny first and foremost, an argument lauded at female characters who have a disdain within fandom due to preference for male characters. In the case of Aerith, labeling her as a Mary Sue would diminish the nuances of her character. In his article “Final Fantasy VII’ Is Surprisingly More Feminist Than We Remember,” Alexander Pan argues that “In contrast to her ‘maiden’ image, [Aerith is] headstrong, street smart, and takes a proactive role in proceedings” (2020). This is reflected in her interactions with the party—joking with Cloud that the Turks could scout her for SOLDIER, threatening Don Corneo when trying to receive information, and punching out an actor who made a sexist remark to her.

By all accounts, Aerith is a revolutionary character for the time she was created. Despite being a female love interest, she still possesses a strong personality and often speaks her mind. However, she is not safe from the misogynistic tendencies of the writers. Returning to Kathryn, she writes early on in her analysis that “Common sexist misconceptions include ideas that women are more spiritual than men, that women are more artistic than men, that women are more in touch with their emotions than men, and that women have stronger social networks than men” (2011). Aerith is shown to have spirituality in her status as a cleric. Her strongest abilities are magic-based and usually relate to healing or buffing the party. Her physical attacks in-game are weak unless they are used for comedy in the narrative, as exemplified above. She is shown to be artistic and creative in her attachment to flowers. Further, she is psychically connected to the planet and mourns for its suffering. Yet, perhaps the most egregious example of Aerith going unappreciated by the writers is how she interacts with Cloud.

With SOLDIER being a symbol of hypermasculinity, it makes sense most people read Final Fantasy VII through the lens of a male power fantasy. Cloud grants the player the chance to be a suave, stone-cold, giant sword-wielding badass who saves the world. Aerith contrasts this masculinity with her femininity, being a soft, staff-wielding, maternal cleric who feels the pain of those who suffer. While Cloud symbolizes what a man dreams of being, Aerith symbolizes what a woman is expected to be in male society. She is a bit sassy and pushy, but by all accounts becomes demure and passive near Cloud. She must rely on him to be her bodyguard against the Turks and has to be rescued by him when she’s kidnapped by Professor Hojo. The same can be said of Tifa. Tifa comes off as masculine and goes against some stereotypes of female characters. Unlike Aerith, Tifa is a fighter class rather than a cleric and relies on her physical strength in combat. Yet, Tifa herself is much more demure than Aerith. She’s reserved near Cloud and struggles to make decisions. She shows hesitancy in killing the fascist regime her world is under and is terrified of the dangers that come. These characteristics carry over into alternate portrayals of the Final Fantasy VII characters in other mediums, showcasing how these characters are understood by players and by the writers themselves.

Cloud Across the Multiverse

There are extensive versions of Cloud Strife already existing in the Final Fantasy VII universe due to the multitude of spin-off games. However, for the scope of this essay, I will be looking at two major portrayals of Cloud outside of the series—his portrayal in the aforementioned game Kingdom Hearts and his portrayal in the fighting game, Super Smash Brothers. The purpose of looking at both of these portrayals is to look at Cloud from two perspectives. Blom writes “Because of their double nature, characters are therefore independent from any given medium, that is, they appear across different kinds of media platforms without needing a specific medium” (152). In other words, characters are partially a form of self-insertion along with being objects in the narrative. Thus, they are not confined to any specific narrative form and can be transported to various ones. Cloud Strife is not specifically confined to the world of Midgar or Final Fantasy VII or even video games for that matter. Hence why we can see him in movies such as Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children, in TV advertisements, or referenced in pop culture. Cloud still serves the same function in all of these different landmarks even if the space surrounding him is unfamiliar. This is exemplified in Super Smash Brothers, one of the fighting games Blom focuses on in her research.

Blom notes how in most stories where the dominant model of understanding characters is through linear storytelling, we are predisposed to rationalizing our characters like how we would in most other media such as television and film. However, fighting games are unique in that they do not rely on linear storytelling as the game is more focused on a random selection of characters for quick brawls. Despite this, fighting game characters “obtain a sense of personhood through art, move sets, speech lines, and short scenes that the player fits together in their mind” (Blom 155). Unlike the characters in most traditional games, fighting game characters are understood through media outside of the game itself or through quick quips within the game. Thus, when you have characters from other games entering a fighting game stage, you must use your background knowledge to understand them rather than relying on box art or writeups in the game’s manual. Cloud is introduced to us in Super Smash Bros. through a trailer that mimics his original game. We first see a trail of light like the opening scenes of Aerith in Midgar (0:12-0:25).

Following this is the logo for Super Smash Bros. with an “X” to denote that they are collaborating with Final Fantasy VII. As the opening music from the original Final Fantasy VII plays in the background, we have a slow shot showing parts of Cloud—going from his boots to his sword, his back, and finally landing on his face. Cloud then has a voice line stating “Never thought I’d see the day,” as Final Fantasy and more specifically Square Enix characters, were rarely included in Super Smash Bros. From there, we see a selection of scenes displaying Cloud’s moveset in Super Smash Bros. along with small scenes meant to reference or callback to moments in Final Fantasy VII—Zelda sits before Cloud with a flower and Pikmin, reminiscent of Aerith, Cloud stands on a boat moaning from dizziness to allude to his motion sickness, Cloud steals the motorcycle that Wario drives as Cloud is shown to be riding a motorcycle multiple times in the series (1:16-1:38). We see how innate player knowledge is crucial to understanding Cloud’s character in Smash. To those uninitiated, one might be confused by the music in the background, the scenes of him stealing motorcycles, and especially the scene of him standing on a boat feeling dizzy. However, dedicated players can comprehend these things and attribute them to the various sides of Cloud, but what sides of Cloud are we seeing? Other than the motion sicknesses, there’s not much that speaks to the complexities that are described above. We see no mention of his journey to uncover the truth of his memories nor his attachment to Zack. Instead, we see the image of Cloud as prescribed at the beginning of the game—someone who is cool, cutthroat, and calculating. What does this mean for players engaging with Cloud for the first time? Instead of understanding Cloud’s character as a nuanced person who toes the line between masculine and feminine, we perpetuate him as someone who is hypermasculine only. The male-power fantasy is reintroduced, with the only caveat being that you have no girls on your side. It’s just the player living out the fantasy of being a smart and calculating man with a gigantic sword to swing around.

One might argue that the analysis above is going too far. How can we be so certain that this portrayal of Cloud is meant to portray a hypermasculine persona? In earlier parts of her essay, Blom writes about kyara, which is effectively the mascot or physical copyright of the characters represented in video games. She contends that “In SSBU [Super Smash Brothers Ultimate], a kyara functions as an amalgam of different versions of the character, minus their story. It requires the presence of the player and their repertoire of knowledge about the character to think of the kyara as a character.” (162). If we are to look at Cloud as an amalgamation of all iterations of him from our personal knowledge, then what do those iterations look like? This is where Cloud’s portrayal in Kingdom Hearts becomes crucial. Kingdom Hearts was penned by Tetsuya Nomura, the character designer for Final Fantasy VII. He would have intimate knowledge of Cloud, his character arch, how he functions and acts, etc. So how is Cloud introduced to us in this game?

Cloud was first introduced at Olympus Coliseum, the world based on the Disney movie Hercules. Sora is given a pass to enter the Coliseum games by Hades despite having been rejected by Phil just earlier. After getting through the preliminary round, Cloud enters with the camera panning over him—starting at his boots before trailing behind him to see his cape, and finally landing on his face as he and Sora briefly look at each other. Phil remarks that Cloud seems off and alludes to the fact that they’ll have to face off against each other at some point. Later, we see Hades talking with Cloud and implying that he’s hired Cloud as a mercenary. Again, Cloud is distant and biting, taunting Hades for being “afraid of a kid” and pointing out the conditions of his “contract,” similar to how he acts at the beginning of VII. As Cloud prepares for what’s to come, Hades remarks that he’s “Stiffer than the stiffs back home” (14:48-15:27). When the battle finally comes—no matter whether you win or lose—Cloud and Sora will be interrupted as Hades releases Cerberus and attacks Cloud, leaving Hercules to fend the beast off and Sora finishing the job. In his last appearance of this game, Sora checks in on Cloud to see if he’s alright and Cloud mysteriously states that “I was looking for someone. Hades promised to help,” and that “I tried to exploit the power of darkness and it backfired.” In the end, Sora assures Cloud that he can still be a good person, and the two part ways on fairly good terms, with Cloud being distant and broody despite it all (27:22-28:26).

We can see how gender permeates these interactions. Cloud cannot be emotional and his weakness stems from his inability to find the good in himself rather than personal flaws. He keeps this detached persona the entire time he interacts with Sora even though this is a point where his vulnerability should come forth. In the original games, Cloud concedes to his feelings whenever he finds himself bested or finds his truth called into question. Rather than having this nuance, Cloud can only be understood through the eyes of the male-power fantasy.

Something important to note here is the difference in ratings when it comes to both games. Kingdom Hearts is rated E for Everyone while Final Fantasy VII is rated T for Teen. It makes sense that the full brunt of Cloud’s trauma would not be explored in a game made for children, let alone a game not about him. However, considering the game does acknowledge some of Cloud’s backstory in the Kingdom Hearts narrative by having Cloud come to Hades to “look for someone,” which could be any one of his deceased friends, it would follow that there should be some acknowledgment of Cloud outside of his masculine persona. Presumably, this is Cloud later on in his journey after his realization about his memories and the loss of Aerith. At this point, Cloud should have synthesized both truths inside of him and be in a much calmer and emotional state. Instead, in every iteration outside of VII, that portrayal of Cloud does not exist. The same goes for Aerith and Tifa, who are introduced in Kingdom Hearts II. Aerith takes on Tifa’s docility while Tifa becomes spunkier and brash. Both are looking for Cloud but neither succeeds in finding him, while Cloud is once again shown to be a brooding loner in search of his “darkness.” While these characters in the original game have interesting traits that go against conventional gender roles, when they are placed in new settings beyond their own medium, the characters must perform gender roles to fit the male power fantasy that players read into the narrative. In other words, Cloud, Aerith, and Tifa play with masculinity and femininity interchangeably but become fully grounded in their given gender when confined to the knowledge of the players. However, it is not necessarily just the transmedia that creates these limiting versions of the characters, but the innate biases of the writers that seep through into the original game.

Looking Towards a Bright Future

Final Fantasy VII was not saved from the constant jokes of racism, sexism, and LGBTphobia normalized in media from the late 90s and early 2000s. One such situation is when Cloud and the crew go to see Don Corneo. Seeing that Tifa has been kidnapped by the pimp, Cloud takes it upon himself, reluctantly, to dress up as a woman and infiltrate the operation. In the course of doing so, we see various violent stereotypes of transwomen and gay men. A bodybuilder who owns a gym is known to wear makeup and wigs and must give Cloud one of his wigs after the two compete in a squatting match. In order to get an item for his outfit out of the Honey Bee Inn, Cloud must sit in a bath with a group of burly men as Cloud comments on how traumatizing and disconcerting the experience is. When the writers decided to start working on a remake of the original game in 2020, they took it upon themselves to give this sequence of events the modern refresh it desperately needed. Not only that, but the game itself exists as a secondary canon away from the original timeline of Final Fantasy VII. In this timeline, fate is being played with and there is the mysterious sense that something beyond the characters’ control is moving the events at play.

While writing on the game Soulcalibur, Blom discusses how one of the titles in the series is meant to be a reboot of the original but with new changes and plot twists. She claims that “The reboot is an excellent illustration of how invisible hands alter perceptions of a character’s authenticity and identity through canonization…as there is now an ‘original timeline from the previous games and new timeline” (157). The same can be said of Final Fantasy VII: Remake. While Cloud must still crossdress, the messaging is much different. The gym owner is now a transwoman named Jules and has a positive relationship with the people she trains. Further, Cloud’s makeover does not consist of sitting with burly men but instead dancing in a cabaret with a flamboyant designer—Andrea Rhodea. While there are still some implications of ill intent by having an obvious gay stereotype be the one to introduce Cloud to the world of dresses and makeup, Andrea also provides Cloud with an interesting message.

“True beauty is an expression of the heart. A thing without shame, to which notions of gender don’t apply. Don’t ever be afraid, Cloud” (Final Fantasy VII: Remake, 2020).

We see how the invisible hands, as Blom calls them, work to change our perspective of Cloud to one that reflects his true arch. Cloud is not just a toy of masculinity. He is not an ideal nor is he something a man should aspire to be. He is just a man, and at that, someone performing manhood as was taught to him. Andrea tells Cloud about beauty but really what he is talking about is identity. Cloud should not be afraid of expressing his identity because “notions of gender don’t apply.” He can honor his vulnerable side while still being a man, just as he can honor his strength while dressed as a woman. He should not fear being misconstrued, misunderstood, or disdained. Because video game characters are extensions of ourselves, this goes for the players as well. The iterations of Cloud that are stoic and brooding are just one part of the vastness that is Cloud Strife. To limit Cloud to that one facet is to limit ourselves to the gender assigned to us at birth. For Cloud to grow as an individual, he must admit that the life he is living is a lie. He was never a First Class soldier who brutally fended off Sephiroth, he was a meek man who stepped in when necessary but didn’t live up to the expectations that were placed upon him. Once he grows past this, he can face reality in a way that honors his integrity. If we come to terms with the lies we tell ourselves based on societal expectations, we can have a much freer existence where we are no longer afraid.

References

Blom, Joleen. “The Construction of Transmedia Game Characters.” Video Game Characters and Transmedia Storytelling: The Dynamic Game Character, Amsterdam University Press, 2023, pp. 151–70. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.7249516.9. Accessed 24 Jan. 2024.

Heaney, Duncan. “What’s so good about FINAL FANTASY VII?” SquareEnix, 2 Feb. 2022, https://www.square-enix-games.com/en_US/news/whats-good-final-fantasy-vii. Accessed 23 Jan. 2024.

Kathryn. “Feminism and Final Fantasy.” Contemporary Japanese Literature, 1 Apr. 2011, https://japaneselit.net/2011/04/01/feminism-and-final-fantasy-part-one/. Accessed 19 Jan. 2024.

McLaughlin, Rus. “IGN Presents: The History of Final Fantasy VII.” IGN, 30, Apr. 2008, https://www.ign.com/articles/2008/05/01/ign-presents-the-history-of-final-fantasy-vii. Accessed 23 Jan. 2024.

Pan, Alexander. “Final Fantasy VII’ is Surprisingly More Feminist Than We Remember.” GOAT, 3 Mar. 2020, https://goat.com.au/entertainment/final-fantasy-vii-is-surprisingly-more-feminist-than-we-remember/. Accessed 19 Jan. 2024.

Powell, Chris. “Crisis Core is Square’s best selling game this year.” Joystiq, 21 Nov. 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20150128170407/http://www.joystiq.com/2007/11/21/crisis-core-is-squares-best-selling-game-this-year/. Accessed 23 Jan. 2024.

Final Fantasy VII. Square, 31, Jan. 1997.

Final Fantasy VII: Crisis Core Reunion. SquareEnix, 13, Dec. 2022.

“[PS4 1080p 60fps] Kingdom Heats 1 Walkthrough Part 4 Olympus Coliseum - KH HD 1.5 + 25 Remix.” YouTube, uploaded by ShadoKurosu, 2 Apr. 2017.

“Super Smash Bros. -Cloud Reveal Trailer.” YouTube, uploaded by GameSpot, 12, Nov. 2015.

in my mind, one of the core themes of FF7 (original) is identity; consider the Cloud-Zack confusion; Cloud's idolization of Sephiroth, wanting to be just like him, only for that image to be shattered; Cloud being a (failed) clone; and how ultimately none of this shit matters in the end: Cloud is just Cloud, whoever he wants to be. so, what I'm trying to say is, this analysis was super cool to read, as it jived with that a bit.

Loved this! Especially found the analysis between Cloud's characterization in FF7 compared to his appearances in other games to be super interesting. Don't listen to the other commenters, they're just idiots that saw a screenshot of the first sentence and were too lazy to actually give your essay a read.